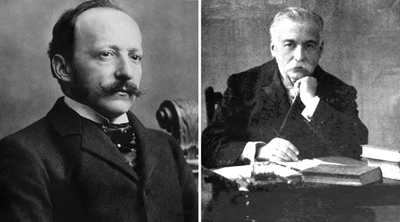

César Ritz

The fabled history of the Ritz begins with the extraordinary story of the “king of hoteliers, and hotelier to kings,” César Ritz. The youngest of 13 children, César was born in 1850 in the Swiss village of Niederwald to a family of poor peasants. Showing an interest in hospitality at an early age, he apprenticed as a sommelier at a hotel in Brig at the age of 15. This didn’t last long and he was dismissed by his boss who declared, “You’ll never make anything of yourself in the hotel business. It takes a special knack, a special flair, and it’s only right that I tell you the truth – you haven’t got it.”

Young César ignored those words, moved to Paris, and worked at several restaurants and hotels throughout his teens. During this time, he met famous French chef Auguste Escoffier, who became his best friend and invaluable mentor.

Ritz moved up the ranks quickly and by 1873 was managing some of Europe’s most prestigious hotels. In the 1880s, he moved from manager to owner and his hotels attracted princes, kings, and prime ministers. It was around this time that he coined the phrase “the customer is always right.”

In 1898, he opened the Hôtel Ritz Paris in a former prince’s residence in Place Vendôme, and here he would apply all of his innovative ideas, changing the world forever.

Grand Opening – 1898

By the time the grand hotel opened in 1898, César Ritz was already known to the world’s most important people. In addition to the social and literary elites of Paris, including 27-year-old Marcel Proust, royalty and business tycoons flocked to the opening—and were not disappointed.

It’s hard to imagine a hotel—much less a luxury hotel—without an en suite bathroom in each room, but the Ritz was the first. In addition to a bathtub, each room also had electricity and a telephone—completely unheard of at the time. Other inventions attributed to Ritz include the king-size bed, indirect lighting, wall-to-wall carpeting, and closet lights that turn on when the door is opened.

Royalty, Artists, and Colorful Characters

The swankiest place in Paris naturally attracted royalty from the start. One story tells of the Duke of Windsor, Edward VIII getting stuck in the bathtub—with his lover—and had to be pried out by valets. Shortly after, all bathtubs were replaced with oversized ones. Another royal, the Marquise Luisa Casati of Milan, reportedly kept two cheetahs in her suite, along with a drugged python that she wore round her neck. Perhaps due to her lengthy stays at the Ritz, she died $25 million in debt.

Many of the most famous artists of the time practically made the Ritz their home. Cole Porter requested grand pianos at all hours of the day and night, and American gossip columnist Elsa Maxwell ordered dinner for 200 at two o’clock in the afternoon.

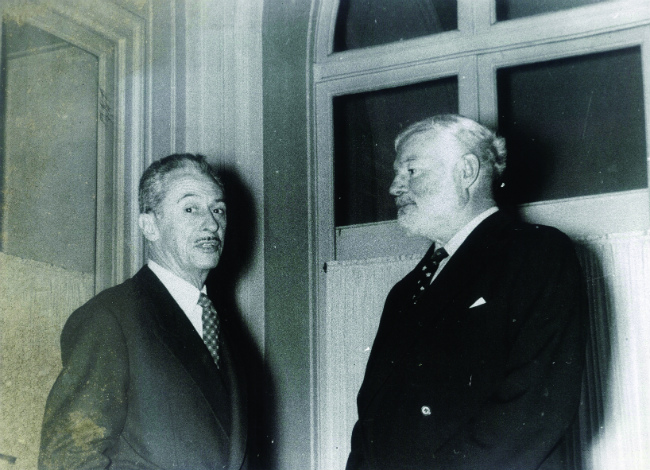

A who’s who list of writers frequented the Ritz, including Ernest Hemingway (more about him later), Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Noël Coward, Proust, George Bernard Shaw, Somerset Maugham, and Graham Greene.

Always bucking the norm, Oscar Wilde hated the modernity of the hotel, writing: “A harsh and ugly [electric] light, enough to ruin your eyes, and not a candle or a lamp for bedside reading. And who wants an immovable washing basin in one’s room? I do not. Hide the thing. I prefer to ring for water when I need it.”

World War II

When the Nazis occupied Paris, they requisitioned all the grand hotels, but French civilians living at the Ritz were allowed to stay, Coco Chanel among them. The infamous Hermann Göring slept in the Imperial Suite surrounded by gems and priceless artwork that had been confiscated from the Rothschilds and other Paris Jews.

The staff continued to run the hotel, turning a blind eye to the fine wines and Champagnes being drunk by the Nazis, along with the likes of Fois Gras, at a time when food was in short supply.

As noted above, Ernest Hemingway was a fixture at the Ritz bar, so when the Americans marched in to liberate Paris, Hemingway took it upon himself to liberate the hotel from Nazi occupation—with only a jeep and a motley crew of military stragglers. His alcohol fueled commando stormed the hotel and accomplished their unofficial mission, then proceeded directly to his old hangout, the Petit Bar. In 1994, it was renamed Bar Hemingway in his honor.

A New Era

By the 1970s, the hotel was showing its age and was purchased for $30 million by Mohamed Al-Fayed. He restored the hotel over ten years, spending $250 million and the Ritz once again took its place as the grandest of the grand hotels.

In 2010, the French Ministry of Tourism established the criteria for a Palace hotel, a notch above the five-star designation, and did not include the Ritz. This outrage, along with competition from newer hotels such as the Shangri-La, demanded that the Ritz once again close its doors for a complete overhaul.

The $450 million makeover was completed in June 2016. Guest rooms were reduced from 159 to 142 to allow for larger bathrooms. A Chanel Spa was added, along with other things expected from a modern hotel, such as a health club. The renovation preserved the “sense of place,” with furnishings being recast originals or new reproductions.

The rich and vibrant history of the Hôtel Ritz is unmistakable, and thanks to the innovations pioneered by César Ritz there, we experience a little bit of it every time we check into a hotel, step into our en suite, relax on a king-size bed, or call for room service.

To learn more about the life of César Ritz, I recommend the first and only filmed biography, Ritz directed by Frank Garbely, and Cesar Ritz Life and Work by Adalbert Chastonay.